Calculating Orbital Velocity

To comprehend how the moon or the ISS stays in orbit, one must first understand that the satellite – the smaller body – is in a state of constant free fall towards the bigger body. The term ‘free fall’ sounds like a vertical drop, but really, the official Wikipedia definition of the term is ‘any motion of a body where gravity is the only force acting upon it’.

Newton’s first law of inertia states that a given object will not change its state of motion unless acted on by another force. For example, the ISS travels at a speed of 7.66 km/s. If the Earth – a source of the force of gravity – were to disappear, the station would continue at a constant velocity (in a straight line with this constant speed of 7.66 km/s), and disappear into space. But because the Earth is underneath it, it constantly pulls the station towards it. This results in a gentle conflict between the station’s inertia (wants to move forward) and the Earth’s gravity (wants to pull station towards it), so the station stays in orbit. Seen this way, Newton saw how the apple falling from the tree and planets orbiting stars are really the same thing, just on a different scale.

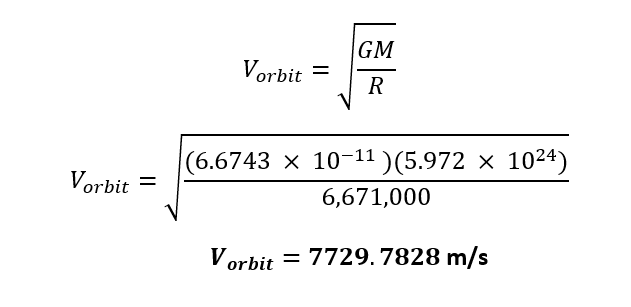

Here is the equation for orbital velocity. It is important to note that this equation is only applicable for systems where one body’s mass is negligibly small compared to the other, like for space station/earth or earth/sun:

We only need to replace these variables with numerical values, and plug it into the calculator. Here’s what they stand for:

G: Gravitational constant. This value, its accuracy proven many times over in experiments, is used in many aspects of astrophysics, extensively so by Newton and Einstein. Important: it is not the same as the lowercase g, which denotes acceleration due to gravity and varies with each planet. The value of G is 6.6743 × 10-11 m3 kg-1 s-2.

M: Mass of the larger body.

R: Radius, in meters. In the case of this equation, it would mean the radius of the center (larger) body (so the distance from its core to its surface), plus the distance from its surface to the orbiting (smaller) body.

Let’s try an example:

A small, newly discovered moon is orbiting the Earth at a height of 300km above the surface. Determine its orbital velocity.

First, we need to find the R value: the radius of the Earth plus the distance of the moon. We can easily Google the radius of whichever body we want to use in the equation; the Earth’s radius is 6,371km, or 6.371*106m, so we add this value to the given distance of the newly discovered moon (in meters).

Then, we plug everything into our equation. The mass of the Earth is 5.972 × 1024 kg.

And there it is! The calculator does all the work, and once you wrap your head around it, you can use it for whatever satellite orbiting whatever object.