Space is a magical place. In its depths lie fascinations beyond our wildest dreams – such as mysterious black holes and swirling nebulae – potentially habitable worlds, and perhaps the secrets to life itself. It’s no wonder that humanity has been reaching for the stars since ancient times. There’s just one small problem preventing us from embarking on that journey: transportation. Try as they might, rockets as they exist today simply are not able to take humans into deep space (beyond the moon); even a lunar landing has only ever been achieved by the Apollo program (though the lack of further exploration can be explained by politics too). As space beckons, an alternative yet fickle technology may provide a more efficient way of exploring the universe: nuclear propulsion.

The traditional rocket – pretty much every rocket you can think of, including the Saturn V, Space Shuttle, Soyuz, you name it – uses what is known as chemical propulsion. Put simply, this involves chemical reactions that release massive amounts of energy; most commonly, the chemicals (called propellants) involved are in liquid form, and consist of an oxidizer and a fuel. An oxidizer – usually Liquid Oxygen (LOX) – provides a medium for the burning of the fuel; on Earth, oxygen present in the air allows for things to burn, but since there is no air in space, rockets need to take it with them. Upon ignition, the oxidizer is mixed with fuel, which can take many forms; the Apollo rocket Saturn V’s massive F-1 engines used RP-1 (refined kerosene), the Space Shuttle’s (and now SLS’s) RS-25s use liquid hydrogen (LH2), and the prototypical Starship’s Raptors use liquid methane.

Before launch, the rocket is loaded with both chemicals in separate tanks, and when it’s time to go, both oxidizer and fuel are sprayed or ‘injected’ at extremely high pressures into the combustion chamber, which sits above the engine bell. So-called hypergolic propellants (used on the Apollo lunar module) combust upon contact, but for many other propellants such as those described above, an ignition (often an electrical spark) is required to ‘light’ them right after injection, and this has to happen extremely quickly; if it is even a fraction of a second late, too much propellant may have already flooded the chamber, resulting in a much bigger kaboom than intended.

All going well, the hot gas is then forced to escape through the engine nozzle, which is located under the combustion chamber. This forms a jet of gas leaving the rocket as quickly as ten times the speed of sound. Newton’s third law states that every action has an equal and opposite reaction; the dramatic exit of the gas in the downwards direction therefore sends the rocket in the opposite direction (this concept also explains how rockets fly in a vacuum).

Each fuel type comes with its own set of pros and cons, some being more efficient than others. An engine and its propellant’s efficiency is measured in specific impulse; it is kind of a proportion between input and output, comparing thrust (the force produced by the engine) against the rate of fuel use. Liquid hydrogen, which has the highest specific impulse, is NASA’s go-to. However, it is somewhat of a prima donna among fuels, requiring a temperature of -253°C (-423°F) to remain liquid (compared to the -183 for LOX), so it needs more insulation. It also has low density (meaning larger tanks) expands quickly (meaning more explosions), and easily escapes through cracks (looking at you, SLS). Liquid methane and RP-1 are untested and less efficient, respectively.

The main problem with chemical propulsion, however, is simply how much of it is needed. Tsiolkovsky's rocket equation shows that the more payload, or mass, a rocket has, the more fuel it needs, which further increases the mass, and so on; in fact, the vast majority of a rocket’s mass is propellant. As explained here, a trip to Mars – even if the two planets are aligned perfectly for the trip – would require 1,000 to 4,000 metric tons of the stuff. Though the Starship, upon refueling in orbit, could carry up to 1,200, it still wouldn’t take us much further than our nearest planetary neighbor.

In addition, this optimal alignment only happens every 26 months, but even then a round-trip would take three years, according to NASA. As a result, astronauts may develop cancer after long exposure to cosmic radiation without protective water tanks, which add further payload (meaning even more fuel). This method simply won’t do if we want to explore the cosmos in person.

Nuclear propulsion, however, could get us closer. The US has been eyeing this technology since the 1950s; in fact, as explained here, it was a significant field of research for the fledgling NASA after its establishment in 1958. But public and governmental support for space exploration dried up soon after the first moon landing (which used a chemical rocket); still, early tests were largely a success. As NASA sets its sights on a human Mars landing in the foreseeable future, it has announced awards to several companies to develop nuclear propulsion proposals in July 2021; three months before that, the Defense Advances Research Projects Agency (DARPA) also awarded three companies with funding for a similar goal, and the US Military announced another such program in May 2022.

Nuclear propulsion is incredibly efficient; in fact, the propulsion type commissioned by the above agencies, known as Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP), has a specific impulse of at least twice that of the LH2/LOX combination favored by NASA (other concepts’ specific impulses have been predicted to be over ten times that, such as this one). The idea behind NTP is not unlike that of normal nuclear power plants. The rocket would contain a nuclear reactor whose job is to facilitate nuclear fission: the splitting of atoms. In fission, a neutron is sent to collide with an atom such as uranium, causing it to become unstable and break apart.

This releases several neutrons as well as the two ‘halves’ of the old atom, which collide with the surrounding matter, heating it up (in a power plant, this matter is water; in a rocket, liquid hydrogen). Gamma rays produced by fission, as well as radioactive decay of the remnants, further heat the substance. In rockets, this superheated hydrogen (2,538°C/4,600°F) is sent out of the engine at dizzying speeds (like in chemical rockets), producing large amounts of thrust while remaining super-efficient.

Due to Einstein’s mass-energy equivalence, we know that a tiny amount of mass can convert into astronomical amounts of energy; in this context, nuclear fission needs only a relatively small amount of fuel to produce enough energy to last a long time. It is therefore possible to fire engines for much longer than on the fuel-skimping chemical rockets, resulting in prolonged acceleration, more flexibility in maneuvering, and a quicker journey. An NTP system could cut down travel time to Mars by 25%. And in the distant future, the safer, more efficient method of nuclear fusion – which scientists have recently used to produce a surplus of energy for the first time – could even replace the fission (NASA has recently begun exploring this, too).

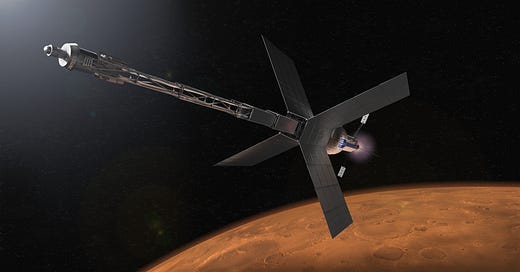

The specific NTP design described above is known as a solid core type; there are many variations of this, but the basic mechanism – nuclear reactions causing an ejection of hot gas – remains the same. There may also be a way to increase efficiency even further with a whole new system: Nuclear Electric Propulsion (NEP). It works by using the thermal energy created by the nuclear reactor to create electricity (like in a power plant) which positively charges particles (ionizing them). These are accelerated by ‘a combination of electric and magnetic fields or an electrostatic field’, and then expelled out of the engines, called ion thrusters.

Save for the nuclear part, propulsion by means of electricity has been done in many missions such as NASA’s 2007 Dawn mission to the asteroid Vesta; here, the electricity was generated using solar arrays rather than a reactor. NEP could reduce travel time to Mars by 60%, and according to NASA, it would reduce fuel by 90% compared to chemical rockets. Relying on a nuclear reactor rather than sunlight – which becomes weaker the further away one is from the star – is a big plus. And though its thrust is quite low compared to other methods, its extreme efficiency – which, again, means acceleration, speed, endurance, and maneuverability – makes it ideal for deep space missions. While producing only one pound of thrust, the system allows for speeds of up to 321,869km/h (200,000mp/h); that’s over five times the speed of Voyager 1, one of the fastest manmade objects in history (the fastest ever, Parker Solar Probe, will reach speeds higher than that as it uses only the powerful gravity of the sun).

But as peachy as all that sounds, nuclear-powered rockets still remain a pipe dream of the spaceflight world, for several reasons, including politics; at least in the US, the actual going-to-space part of governmental spaceflight is negligible compared to the money the process generates for private companies, jobs it creates, and voters it supplies, so the sense of urgency just isn’t there (also, as explained here, nuclear space projects faced severe regulations and required approval from multiple agencies plus the president since the 1970s; only in 2019 did President Trump declare that smaller projects needed only NASA’s approval). And even if everyone was gung-ho about going to deep space (which, in the US, is not the case), the fact remains that nuclear propulsion, being, well, nuclear, is a tricky and dangerous mechanism.

Nuclear power – as opposed to propulsion – is almost standard practice in space; the Curiosity rover, for example, charges its batteries with decaying radioactive plutonium. Over thirty satellites using a nuclear reactor rather than just the element to power themselves currently orbit the Earth. Save for one American, these are all Soviet, and some of their predecessors have proven the danger of this technology in Earth’s close vicinity; in 1978, Kosmos 954 (its reactor powered by uranium) disintegrated over Western Canada. The dust and fragments, which covered 400 miles, were found to be radioactive and could have killed anyone in contact with them in the first ‘few hours’.

Sticking a bunch of people into a tin can with one of those things and sending it out to space does not bode well, especially given that even your garden-variety, tried and tested chemical rockets tend to blow up on the launch pad every now and then. A nuclear rocket doing that… well, it wouldn’t be good. But nuclear rockets don’t have the thrust of the chemical ones anyway, making it harder for them to escape Earth’s gravity and air drag, so it is actually more efficient, let alone safe, to launch on a traditional vehicle and switch on to the reactor once in space. On board, shields as well as the propellant tanks would protect the crew, according to Anthony Calomino, a materials and structure research engineer at NASA’s Langley Research Center. The rest of the radiation will escape into space, which is thick with cosmic radiation anyway.

The most obvious obstacle, however, is building them; the technology is demanding any way you cut it (that’s not even counting the danger that lies in testing it). NTP produces incredibly high temperatures, which, according to Calomino, not many materials can withstand. As for NEP, which is even more untested than NTP, the challenge lies in making its many complex subsystems work together before even thinking about sending it to space. And while nuclear reactors already operate in space, making them work for rocket propulsion as opposed to powering a satellite will also require some adjustments.

In February 2021, NASA stated it is considering developing either propulsion mechanism for a trip to Mars, but the DARPA and NASA contracts from that same year, which fund only NTP, contradict this. Roger Meyers, a NASA consultant, believes that this is once again due to lawmakers ‘wanting to fund certain centers’ in their districts, which NTP might be better suited for.

But again, NASA is not the only interested party. Both the US military and DARPA have commissioned NTP proposals in the last year or two (DARPA’s program has now entered its next phase, aiming for a 2026 launch), and it’s a pretty safe bet that that kind of money doesn’t just come from an innocent love of space. According to US Air Force Major Ryan Weed, program manager for the Pentagon’s Nuclear Advanced Propulsion and Power, ‘advanced nuclear technologies will provide the speed, power, and responsiveness to maintain an operational advantage in space’. And since NEP has less thrust than NTP – its endurance making it more suitable for deep space exploration rather than orbital shenanigans – NTP is the clear winner, despite NEP’s efficiency. It is therefore clear that President Trump did not lift the regulations on (smaller scale) nuclear space activities in 2019 out of the goodness of his heart; a nuclear-powered trip to Mars would just be a byproduct of increased military activity in orbit.

And Earth’s orbit is already overcrowded, with millions of bits of space debris – an ever-growing amount – hurtling around the globe at unthinkable speeds. A rocket going to the moon, Mars, and beyond would only pass through the debris field once, but vehicles staying in orbit are at a constant threat of being hit. Unless this problem goes away, we may eventually reach a stage where nuclear spacecraft coexist with deadly space debris; the vast majority of debris is too small to be tracked, but can still crack a hole into a rocket. If a nuclear rocket is hit in the right spot and disintegrates, it would not only kill its crew, but the vast amounts of new debris would be radioactive, like those resulting from Kosmos 954.

This scenario just gets better considering that rocket-powering uranium would be at an enrichment of 19.75% (power plants use around 5%); 20% enrichment would put you on your way to build a nuclear bomb. If the US goes ahead with space militarization by means of nuclear rockets, it won’t be long until other countries follow suit. That will create competition, and sooner or later, one government may decide to increase enrichment allowance for better technology. Then we’ll have a problem. And regardless, uranium can be enriched using several different processes, so the line between a country possessing only rocket-grade or weapons-usable uranium may begin to thin.

A knack for exploration, including space, is part of what makes us human – but so is a knack for war. Nuclear technology – including its use in rockets – exemplifies this duality, potentially opening doors to both space exploration and an increase in orbital military activity. While nuclear rockets are still in their embryonic stages, will the extraterrestrial ventures be worth possibly escalating Earthly conflicts into space?

Thanks for another interesting read!